I mentioned that most of the wines I buy are $20 or less, and that I have developed my own compass for those purchases. But, I do frequently splurge $50 (or more!) to get a bottle I’m really curious about. For those splurge purchases, I’m virtually blind and rely on the expertise of others to “advise” or “guide” me. Wine scores are one of the resources I use to make those splurge buys. The sources I consult most regularly are Wine Spectator (WS), Wine Enthusiast (WE), and, increasingly, Vivino (V). There are obviously other sources (Vinous, Wine Advocate, Suckling, etc.) that I have little-to-no experience with, but for the wines I buy, WS, WE, and V offer good coverage of reasonably available wines that I’m interested in, so I focus on them [1].

I am also wine score skeptic. I absolutely believe commercial and emotional forces push reviewers to award higher scores, especially scores over 90. Scores of 90+ are heavily used in labeling and marketing of wines. Wine magazines rely on advertising from the wineries whose products they score, and the pressure to “reward” advertisers must be there. Also, wine reviewers are subject to pressure to positively review wines—whether it is to please the person in front of them, or to get better access to wineries and wines in the form of trips, conferences, and other perks. It must be noted that WS and WE both assert they have put in place protections to insulate reviewers–its worth looking at these. About Our Tastings | Wine Spectator Our Buying Guide and Blind Tasting Process | Wine Enthusiast (winemag.com)

My skepticism is translated into a general consumer fear: that I’ll rely on a very positive review and high score, splurge on a bottle of wine, and feel “robbed” if the wine doesn’t live up to the expectations generated by the positive review. Given the amount of money I’m spending on wine, I decided to take an objective look at the wine scoring systems I refer to, with the goal of minimizing this “robbed” outcome.

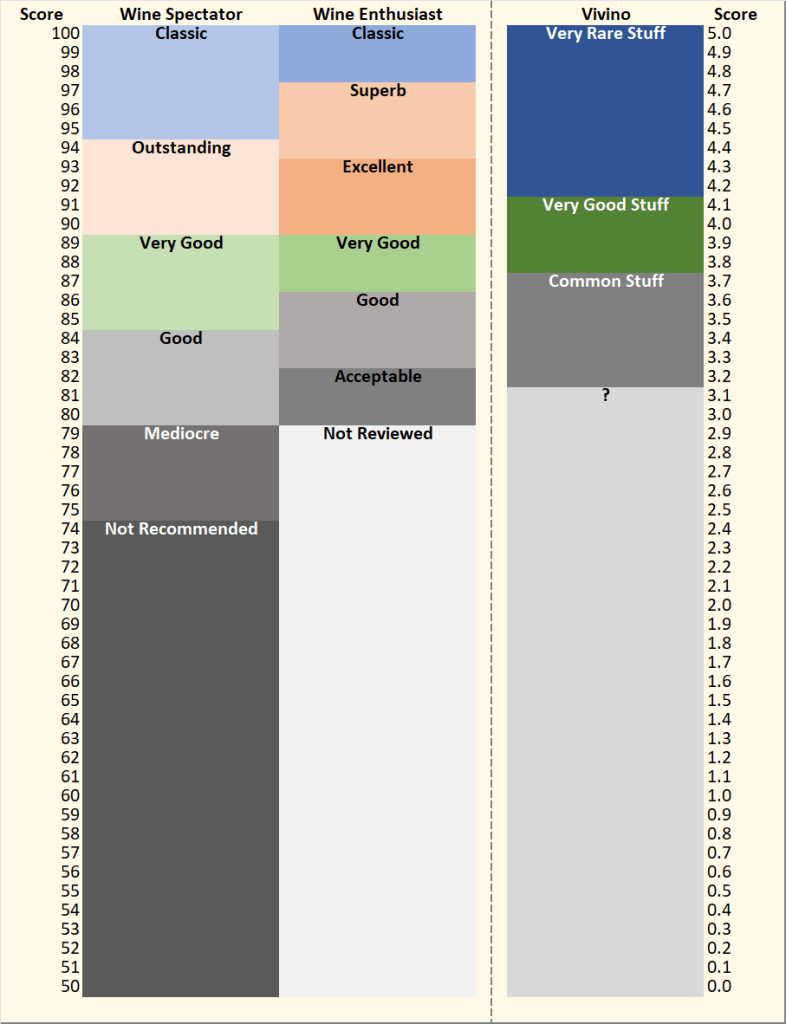

First, I took a look at the scoring systems themselves. On first blush, the three most prevalent scoring systems look very different (see figure below). In my opinion, the differences are somewhat ephemeral.

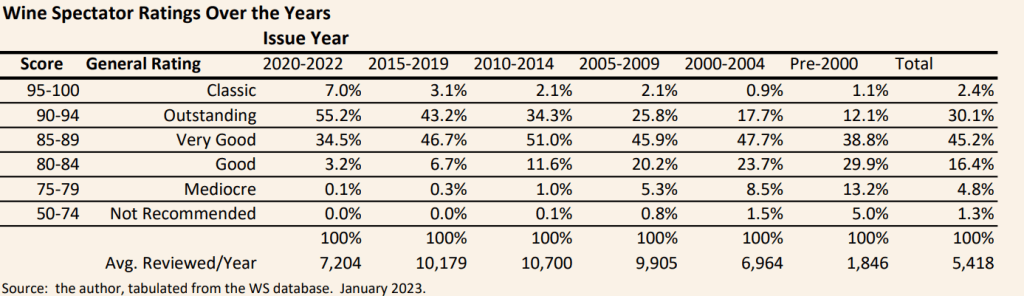

- One non-difference: WS scale starts at 50, while WE does not review wines below 80. But, in fact, WS scoring in practical terms doesn’t use the 50-80 part of the scale anymore—in 2020 to 2022 issues, WS gave less-than-80 scores to about 0.1% of all wines reviewed (see table). The below-80 category was heavily used by WS in the past (e.g. 18% of wines reviewed got less than 80 scores in years prior to 2000!), but it is essentially unused today.

- Second non-difference: There are semantic differences between WS and WE in the translations of the numeric scores into verbal categories. Those differences (e.g. between “superb” and “outstanding”, or the boundary between “good” and “very good”) are highly subjective and are meaningless to an average consumer, who, based on my experience, tends to equate the scores anyway.

By the way, the “inflation” of scores shown in the above table can be interpreted in a few different ways. One interpretation is that true inflation of WS scores is happening–i.e. that wines of the same quality are being given higher scores over time. The other interpretation is that wines overall are improving over time. Finally, it may be that WS is selecting better and better wines for review over time. It may be a combination of all of these changes. Nothing in the analysis I did allowed for me to weigh in on this issue, but my skepticism leads me to believe that true inflation is at least part of the change. It should be noted that WS searchable database is unique in allowing tabulations of their full database, with the capability of specifying a wide range of cross-classifying variables for the tabulations, which puts into consumer hands a powerful tool.

Comparing Three Ubiquitous Wine Scoring Systems

Vivino presents a unique scoring system, largely (but not totally) independent from the WS/WE systems. First, Vivino is a social network, with reviews coming from a largely unknown group of app users. This contrasts to the expert reviews of WS/WE. Vivino’s scoring system is a 1-5 scale, with two options for an individual user to input a rating: using the browser version of Vivino, scorers can pick a numeric 1-to-5 rating by 0.5 increments; using the Vivino app, scorers can input a 1-to-5 rating by 0.1 increments. Vivino does not offer any explanation of why different ratings options are available, and Vivino combines the to for an aggregate score in 0.1 increments. Vivino sort of skirts between the common 1-5 integer scale used for many online consumer purchase reviews, and the mysterious (to most app users) 100 point wine scoring scale. Vivino itself does some “translation” from their scale to the 100 point system, but don’t say exactly how they do it. In the figure below, I present my own translation, which I’ll discuss more below. It is fairly simple: Vivino 100 (V100) score = 80 + (Vivino5 score minus 3)*10. So, a score of 3.2 in the Vivino 5-point scale (V5) would translate to 82 in the WS/WE 100 point scale for this piece: 80 + (3.2-3)*10 = 80 + 2 = 82. A Vivino 4.5 translates to 95 on the V100 point scale: 80 + (4.5-3)*10 = 80 + 15 = 95.

As a social network, Vivino suffers from all the same potential problems that all networks do: no common calibration of scoring, each scorer brings their own definitions; potential to be manipulated by biased reviewers (e.g. a winery creating many Vivino accounts and biasing early scores of a wine); and user error (e.g. dropping a rating onto the named wine without specifying the correct vintage or specifying a vintage at all). The tradeoffs to these potential problems are ubiquity (many, many reviewers, with most commercially available wines scored) and currency (i.e. wines come up on Vivino very soon after release).

One major concern about abuse of Vivino is exploitation of what I think is the biggest source of bias in the platform: presentation of the current rating of a wine to a new rater. By allowing a new rater of a wine to see the current rating, it turns the new rating from and honest, full assessment to a “agree/disagree” decision with the current rating of the wine. A wine maker or marketer could use false accounts to post a rash of positive reviews of newly released wine, and thereby bias all later raters of the wine. Vivino could do to specific things to allay this concern. First, it could provide information on the variation on ratings broken into sequential blocks (e.g. the first 50 ratings, ratings 51-100, 101-150, etc.). If new raters are unbiased, the variation of ratings for each sequential block should remain uniform. If new raters are biased by the current rating, the variation of sequential blocks would reduce with each successive block–e.g. the 3rd block would have less variation than the 2nd, etc. Second, Vivino could post information about how it identifies and purges fake accounts.

In the next two posts (coming soon…), I take these three wine scoring systems, and do objective analysis of them.

#4 Post: I look at 220+ available red wines that were scored by all three systems, and provide statistics on the consistency (or really, the LACK of consistency) of the scores for the same wines.

#5 Post: In doing the work for #4 Post, I noticed patterns of inconsistency of specific reviewers. In this post, I “score the scorers” and provide my take-aways on how I am using both scores and reviews moving forward.

Footnotes

[1] I recently subscribed to Wine Advocate, will be exploring its wine database, reviews and scores over the next couple of months. I may update this post if I learn anything from this exploration.